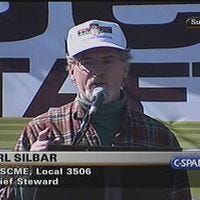

We feature a great interview with Earl Silbar, a radical fighter over the years when he helped lead protests during the Civil Rights and anti-Vietman days, to his leading the part-time Chicago City College teachers as the union steward and strike, to his joining CORE to fight against the city powers. A transcript of the interview is included below or you can listen to the audio podcast. Enjoy!

Okay, hello Second City Teachers.

This is Jim Vail and I'm more than honored to have on the line Earl Silbar.

We go back a few years, back in our City College days.

He is another one of my big heroes when it comes to fighting the powers and working in the fight in education.

We were together at the City Colleges and up through Chicago Teachers Union, CORE, and our whole fight.

And Earl's got a fascinating history and knows so much

Okay, Earl, welcome.

Can you tell us a little bit about your background, where you come from?

SPEAKER 4

Sure.

I don't know how much you want, so I'll keep it short if there's something you're interested in asking.

I'm born and raised on the south side of Chicago.

My mother was politically liberal.

My father was a communist.

and my mother did not want political discussions at the table so we had a limited number of them.

I wasn't a typical redneck or baby in that regards.

By the time I was finishing high school I was aware of the fact that a very small number of people controlled the destiny and the lives of very many because in 1959 when I was a high school senior there was a steel strike that lasted, I don't know, well over a month.

And it became very clear that the board of directors of U.S. Steel and the other steel companies wanted to enforce what would have been harsher conditions on the workers.

And the strike was, in that regard, a bitter fight.

So I went to college with the idea in my mind that we had a political democracy, but an economic dictatorship, if you will.

And I joined the first socialist club I ran across, which was really a Democratic Party reform group, but it was what it was.

And I learned political lessons that there were such things as coherent ideologies and of course we had to fight our internal enemy which was people who wanted a labor party, a working class party which ironically I am strongly in favor of and have worked towards.

So 1963

I went to the march on Washington and it was a very liberating experience.

The desire of black and whites who were on the train going to the march together was wonderful.

And it made real the possibility of real solidarity, mutual support, and love; it was just extraordinary; anyway um so I went and i traveled and i worked and when i came back in 64 i got active i went to Roosevelt University and i got active with uh friends of snick so i was a little foot soldier in what we consider the civil rights movement and then when snick uh basically kicked out white people for black power.

I joined an anti-war group of about seven or eight fellow students at Roosevelt and we decided that we would organize against the war.

And so we put out literature and held meetings and brought in speakers and had confrontations with our management, the president, members of the board including one who um whose company made tests to determine who would and wouldn't be drafted on to an effort so we organized against that and we were successful in forcing him off the board. As I recall anyway several years of anti-war organizing and I'm helping with my fellow radicals from SNCC and civil rights work.

We organized the first community to end the war in Vietnam and Chicago and organized mainly to talk to people going to work or coming from work on transit to CTA.

And we led the first marches in Chicago and that led me also into the struggle of students against what we saw as lies and misrepresentations in the classroom.

So it brought us into work with student daily experience.

Let me stop for a second.

VAIL

Okay, so, yeah, Earl, did you, when you were organizing against the war, this was when you were in college and out of Roosevelt?

In the 60s?

EARL

In Roosevelt, we had an anti-war committee of Roosevelt, which we named Roosevelt University Students Against the War.

And then we, together with some others, organized the first Chicago Committee to End the War in Vietnam.

I was still a student at Roosevelt, yes.

Well, I had one of my best friends who we're still friends 60 years later who was a supporter of what was his name, Jim? He ran in 64 against... You mean the presidential candidate?

SPEAKER 3

Yes.

Eugene McCarthy or McGovern?

SPEAKER 4

No, this was before.

This was before 64.

He was a Republican.

So my friend was a Republican, was a former Republican.

When he realized that the draft had come for him, he started to come to our anti-war activities.

And there were many such people as well as liberals and radicals who were against the war, but lots of people were affected by the potential of the draft.

And the draft was not an abstraction, and I did not have a student deferment.

My children are born in 66 and 67.

And I never registered for a deferment.

But I must have had, they must have granted me one.

Anyway, it didn't affect me.

Personally, I was never drafted.

And they weren't breathing down my neck.

But it certainly made lots of people question what was going on.

VAIL

Right, right.

And what was that like, that whole anti-war fight back then as far as in the city?

I mean, I've heard crazy stories of burning down the draft boards and, you know, the whole fight with the power.

It was a quite radical time that we later, you know, just hear stories about.

Any stuff you remember?

EARL

Well, sure.

We brought in speakers who gave talks about Napalm, which was jelly gasoline, which was dropped on the Vietnamese, and it was generally a white pox or something, and it would burn people down to the bones.

It would literally burn that flesh off their body.

And so that brought an emotional response from people because it not only was personal, but it was one you were expected to do to others.

We had ticket lines that shut down the place where they did the testing, as I mentioned.

We didn't burn down any buildings.

But we changed a lot of minds and we helped to contribute.

We were one of the small streams that were feeding a mighty, mighty river.

Because in fact, within four or five years, the strength of numbers and the radical activity of the anti-war movement.

Lots and lots of young guys who were being drafted had been exposed to it, and together with the experience of what they were doing, it undermined the ability of the military to carry out their tasks and to wipe out the people in Vietnam.

So I don't have dramatic stories for you, but it was a very intense time.

and we were constantly taking up arguments or information that people were getting, students in particular were getting from the media and the government lies and we would be countering them and then we would be focusing on the administration and the president of the college, Rolf Weil was a German born Jew who escaped Nazi Germany

And when we confronted him in front of others about the collaboration with the war, he said something to the effect that, well, we're just following the rules.

And we pounced on him and pointed out that that's exactly the same excuse that the Nazis had.

So it was exhilarating and it was, I wouldn't say tedious, but it required a lot of time and effort, and we believed in what we were doing, and I came to see that it was related to that same thing that I recognized when I was in high school.

Because we would do research and we read what Eisenhower wrote about North Vietnam, that if there had been an election that Ho Chi Minh would have won in Vietnam as a whole.

What kind of minerals were involved?

What was at stake?

It opened your eyes to the bigger world and you had to confront things.

So that was exciting, especially when we forced the administration to change some of their policies.

It's an incredible feeling that most people don't have anymore.

But with the strike waves that's going on in the last two years,

VAIL

Now, what work did you have as far as earning money?

EARL

My first real job for money was driving a Good Humor truck for three years and then around 1966-67 I was working in factories, then I went back to school, then I worked in factories on the north side of Chicago, on the west side. Canne, Continental Canne Company, Stewart Warner, mostly working with either clean up or working as a machine operator, and facing the challenges of the job, which was making sure that I didn't lose my fingers or my hands.

I'll tell you, I was working at a small machine shop.

And there was a union meeting, so I went to the union meeting, and I just asked if I could see a copy of the contract.

That's probably what you're thinking about.

And the union said no, but if I gave them my name and my address, they'd send me a copy.

And like a naive person that I was at the time, I did get it.

And the next day, my card was no longer in the check book in the file where you would put your card before you would stamp it with a time stamp to show whether you came in when you left.

So I was fired because the union was literally working with a company because that's the only way that would have happened.

So I wasn't asking to see the budget, but I was asking to see the union contract.

And I learned that unions are not a unilateral, always a good thing.

VAIL

Yes, okay, so you were involved in radical politics to end the war, racial justice, you had joined the PL for Workers party.

You were looking to, you know, just change the system and it was that spirit in the air at that time.

Did people feel there was possibilities for that?

EARL

Absolutely, yes.

Part of it was I got hooked up through SDS and then through SDS with Progressive Labor.

And their central idea was that the war was an imperialist war, it was not a big mistake, and that the beneficiaries of imperialism were the same people who ran the corporations, like my experience with U.S. Steel, Steel Strike of 59.

So the connection became plausible, and that's just a nice idea, because more and more of the young people were being affected by the Civil Rights Movement.

Black people, mostly working class people, were forcing change in a system that had been getting worse and worse for a century after the Civil War.

And the idea, the actuality that grassroots people, maids, carpenters, and so on,

could band together and force change was a very exciting reality and it gave substance to the idea that the working class could force change.

And the communist idea that the working class, because of the need to work together for common goals, could actually

created a new society based on human needs and everyday people having the power to change things which we identified as a dictatorship of the proletariat and others saw as socialist revolution and had different words for but what I've learned is we were all talking about the same general kind of a radical transformation and because there were so many radicalized young people in the workplace

The idea of working class revolution or at least working class action being able to stop the war made sense because we saw wildcat strikes.

In 70, I think it was 71, black postal workers in one post office in Brooklyn went on strike because their conditions were really hard.

And it triggered a national strike and the workers were radical enough

that they refused to follow the union leaders who told them go back to work we'll negotiate this and they were like no we're going to strike until we get what we need and that was a break from passive forms of union activity before and then in that sense it was organic it grew naturally it didn't happen because some groups said you should do this you should do that

It was the needs of the time and it was also the opportunities because of the radicalizing impact of the Civil Rights Movement, the Black Liberation Movement, and the anti-war movement.

And that was probably the most exciting because it opened the door to a whole new way of life and looking for ways to build towards that future.

SPEAKER 3

You're still active.

When did you start getting into teaching or what did you do after, I guess, we're getting to the 70s, mid-70s, Vietnam War ended.

What happened to you next?

SPEAKER 4

I was very depressed.

I had been fired or kicked out of Piedmont in 72.

And they did not, me being in leadership, did not

I'm sorry, what was your disagreement with them?

I know it can get into a big thing, but just a quick...

What information we could add to the mix.

And the outlook was towards an alliance of students and workers against the war and against the system.

And after there was a convention where the different factions split up in 69, there was an SDS convention of almost 2,000.

After that split,

SPEAKER 4

Progressive labor led a faction of about a thousand students in many different SES chapters across the country.

But instead of continuing with a successful and exciting and promising strategy, they basically came down with a strategy that said campus workers to relax.

So if there were postal workers on strike, or UPS workers on strike, (nope, can’t join in)

and I wasn't terribly shy about sharing that plan with him so he decided that I was no good and I was quite startled and within a year or two I was very depressed in the mid 70s to the late 70s it was a very depressing time but a friend of mine was involved in a discussion that the study group

and he asked me if I would join and I found comradeship and realized discussion of different points of view from the left and I would say that reconnected me.

I reconnected.

So I've probably worked in about eight factories over about four or five years.

I had one particular incident in Stuart Warner which made parts for cars.

We had a union there too.

It was an IBEW local, 1031 as I recall.

And there was electrical fire in the factory.

So we were told not to come in because I was working midnight sheds.

The union contract said that if through no fault of... I'm trying to remember the word, the language.

The union contract said that if workers were notified not to come in because of things outside of workers' control that you would be paid for either four or eight hours pay.

So one of my friends

at work said, Earl, why don't you go in and talk to the manager and the union rep and see if we're going to get paid.

So I did.

And the union rep told me we wouldn't get paid because it was considered an act of God.

And that was ridiculous electrical fires being an act of God.

It's just that they didn't maintain the system.

and they didn't want to pay us money.

And so that was just one more experience.

It may sound like I'm against students, but I would say it was more like getting inoculated or getting a shot for COVID.

And it helped me to understand the reality or the complexity of the situation.

And it also

prepared me for similar experience in education work as well.

SPEAKER 3

Okay and so then, so after that experience did you go into teaching or what happened next?

SPEAKER 4

I went back to school.

I got a bachelor's and a master's in education and I went, I wanted to be a history teacher in the Chicago Public Schools.

but they hadn't been hiring people for years in the history, so I went and I was a day-to-day sub at Little Blue Technical High School in Southside.

And I loved it.

I mean, I would have paid a big price if I couldn't have the money and the contacts to get a history teaching job there because the students all had to read at an 8th grade level, which meant that they could deal with much more sophisticated and complex materials.

And it turns out that the students were, for me, a joy to teach because they were open-minded.

At the same time, they had strong beliefs.

But you could engage with them over science, over history, over economics, over many things because it's your day-to-day.

So you teach whatever you teach your replacing day.

So whether it was gym or whatever.

So that was an experience.

I taught there for two years.

Something like that.

SPEAKER 1

Okay.

Okay.

SPEAKER 4

Yeah.

Um, I wouldn't say that they were radical, but it was a joy to teach with them and to be with them.

And, uh,

Yeah, that was a good experience.

I also saw that there were teachers who basically sat at their desk and read the paper, and when the students would complain or ask about things, they would tell them, I got mine, now you go get yours.

There was a hand.

And at least some of the teachers were very self-centered.

just preoccupied themselves very much about just seeing how much money they can make and no concern for the students whatsoever.

And of course, I found other teachers who were just the opposite.

So I was being introduced to the reality and the complexity of the workforce and the working class.

Yeah, I wasn't cynical.

SPEAKER 3

So you did that, so you were a substitute teacher at Lindblom for a couple years and then what?

SPEAKER 4

Well I got a job with a program called 2001 which was a government program that paid students to prepare for the GED exam and that's where I got introduced to teaching GED preparations material

which I ended up doing for 27 years for the City Colleges and that's where we met.

SPEAKER 3

Well it began, I got a job there

SPEAKER 4

I think it was March 3, 1979.

So there was an organizing drive and it was called the Organization of Hourly Training Specialists.

That's what we were called in those days.

And there was a tremendous amount of radicalism among the teachers with all adult education.

People who were preparing students to pass the GED exam.

And we had English as a Second Language ESL teachers teaching immigrants.

And there was literacy, basic literacy for people who were native English speakers, Americans.

But very low reading levels.

So there must have been like 1500 of us and there was an organizing drive already going on

And so I got involved at that time.

So there were meetings and at that time we would go downtown to one of the campuses and the administration set up workshops.

And we would basically organize ourselves to prepare.

And we would take over the workshops, not physically, but with our arguments and what we were talking about and what our conditions were and what we should have.

So we took their workshops and turned them into our organizing.

And it was, in essence, we were continuing what we've been doing as anti-war and civil rights activists.

And so it was the same stuff in different locations.

And for me personally, it was

SPEAKER 3

And you became then the union steward, when?

When did you start to represent the union, getting involved with the union politics and all that?

SPEAKER 4

We started a committee, a handful of us started a committee, and we went around to the different campuses with literature and people who were most interested contacted us to exchange information.

And so we grew, we had an organizing committee of, I don't remember, maybe 20-25 people from different campuses around the city.

So then the organizing committee went around and interviewed people from different unions.

And the organizing committee decided to join AFSCME, American Federation of State and Municipal County Employees.

And a friend of mine and I, we both had union experience.

Our experience was that AFSCME was not a strong fighter.

They were strong talkers.

But most people liked what they heard.

And so we wanted to join AFSCME.

And I was, along with 20, 25 others, I was part of the organizing committee.

And so then we chose a negotiating committee to get our first contract.

And I was on that one of all the negotiating committees.

Now we've been, maybe 1988, something like that.

And so we had an union organizing drive and we won like 90% of the vote and that's when we got our first contract.

And that was my first, that was my introduction to union activity as a worker in education.

and the Earl Silbar Test right now.

SPEAKER 3

I remember some of it.

You're talking about Robert Earl Granderson and right away

SPEAKER 4

We found, when I say we, I mean the people who were active on the organizing committee, there were different approaches, and they broke down around two different perspectives.

One was we are there to back up whatever the union people say and what they want, and the others were what I would call radical democrats, small d, and we believed in, we had organized, and we had had struggles,

where the people who were affected were the people who made the decisions.

The union, meaning paid staff people, will make the decisions for us and we will try to carry them out.

Is that clear?

SPEAKER 1

Yeah, absolutely.

SPEAKER 4

Even before we had our first contact, it was very clear that there were two camps, so to speak.

I was one of a number of people who had been active in civil rights, who had been active in anti-racist, and active against the war, and were organizers.

And we practiced, as best we could, the idea that, as I've said, the people who are affected make the decisions.

That was our goal for society as well.

And so, it quickly broke down into two camps.

and for example asked me promised us that we could set our own dues schedule but it turned out in the negotiations that the first thing that their negotiator put forward was that for a dues check off and how much you're gonna get and so on and so forth so that spiraled and became more and more intense and

Yeah, that was pretty much the basis of it.

And I was startled to find that a good number of the more conservative people were black teachers and that only a minority of the black teachers

By 1979, 80 and 81 were radical.

My experience in civil rights is very different.

And what you're referring to is where our political opponents, we're teaching at Kennedy King, were spreading rumors about several of us who were organizing

with a Radical Perspective.

And for me they were passing out, they were spreading rumors that my father had died and left me an island in Canada, that I was rich.

And also played the race card in terms of these white people just want to use you and all this kind of stuff.

You could say it furthered my education.

SPEAKER 3

Yeah, I remember that.

SPEAKER 4

It was very... I could see that there were conflicts and contradictions everywhere.

Right.

And the idea that union is automatically the answer or that blacks are automatically radical just wasn't true.

And it became more complex.

Right.

And we had to learn how to deal with it or get spun off to the side.

SPEAKER 3

Right.

Actually, I think it was.

You're right.

It was 2000 to 2003.

So...

SPEAKER 4

There was a group of us mainly centered at Truman College, which you were a part of, of course.

And we were the radicals who survived those other years.

And there's some new people to come on board.

And so we ran a slate of people for union office.

And we campaigned across the city.

And we would set up meetings where we could explain

what we were for and what a strike would mean because most people including me had never been on strike before and didn't have any experience so we drew on the experience of other teachers who had been on strikes to prepare ourselves and so we organized we went around the city and set up meetings at break times because the union contract gave us I think it was 15 minutes or 20 minutes

a break time and we would set up meetings and come and talk for five minutes and then respond to questions and give people's phone numbers and whatever to stay in touch and we had people who were researching the budget and one of us, Ron Rohde, discovered a 90 million dollar slush fund that the city council administration had from taxes that were paid by the city of Chicago.

New City of Chicago I collected and there were a line item, if you were a homeowner, there were a line item in your tax note for City Colleges and it was not, it didn't have to go for any specific cost.

So once we had that, we took that information around and said City Colleges said they can't afford it, but they're sitting on $90 million which would afford us X and Y in terms of health care.

In terms of living wages we were only making I think around eight to twelve dollars an hour Which is not very much money and certainly not enough to live on into retirement age.

So I remember meetings after meetings after meetings and Sue was our president

She was a candidate for president and she was elected, and all of our offices were elected, including me.

And I was made Chief Steward.

Sue was president.

SPEAKER 3

Sue Schultz, right, was the president.

SPEAKER 4

Right.

And we would just constantly be talking to people and reaching out and researching the information to help answer people's questions or concerns, because everybody was afraid they'd get fired.

And even though we weren't being paid that much, something seems better than nothing in most circumstances.

So we went out for three years talking to other stewards, which I would do as part of my work as Chief Steward, but also talking to members in every conceivable location we could find them.

And after three years, we had a strike authorization vote, which

carried by something like 70-75% across the city and over 90% of two of the largest campuses.

So we were ready to go.

We were in negotiations in 2003 and AFSCME, the state organization named Council 31, was reluctant to authorize a strike.

So the negotiating committee, which included the more conservative as well as the more radical voted unanimously to have a sit-in at the union office unless they authorize the strike because they were the legal recipients of the contract, not us.

So the contract is between the council and the city college administration and not us as teachers.

So we have an indirect relationship.

So anyway, so we voted unanimously to have a sit-in in the AFSCME offices if they didn't authorize the strike.

So they authorized the strike and then about five days before the strike was supposed to take place, the council's representative told us that they were going to reverse their legal authorization and that anybody who went out on strike

I remember, yeah.

uh god who was the i think you represented us because you were you were at truman you represented lakeview as the outpost yes but that's true but i remember having volunteers strike coordinators i remember what we called ourselves for each campus for each large unit and it was either it was either you or somebody maybe jennifer carver

I had talked to a number of people in the preceding week or 10 days before the strike

And yesterday's the possibility that AFC wouldn't actually support us.

But it was too horrific of a thought that we would have to fight management, which we were well prepared to do.

And we would have to fight the council and take it up in the Federation of Labor, which is where all the unions met to discuss common business and common affairs.

The idea that we would have to fight the union

It just took the wind out of people.

And it was devastating.

And most of the active people who've been involved in organizing, because it wasn't just the officers, there were other people, even yourself, who haven't really dressed nice and so on.

It was, you know, it was devastating.

SPEAKER 3

Yeah, that was tough.

I just remember in that fight, the thing that stuck out for me was the sick day.

We didn't even get, I don't think we got any sick days.

No, we didn't.

SPEAKER 4

What we got in order to settle is AFSCME found that there was still enough resistance among us teachers and anger and resentment that they negotiated sick days.

and maybe it was sick days and also it was health care coverage for a certain like 120 of the most senior teachers so we came away with something even if our spirit and our morale was really destroyed.

SPEAKER 3

Yeah, yeah it was a tough time with its ups and downs of organizing and all that.

You had talked briefly about decertifying, getting another union more close to education, but that was a risk.

I remember you were saying that, too.

Not having a union at all could be very... I mean, trying to get another union was another risk that we talked about.

But yeah, the whole thing was tough.

SPEAKER 4

That's right.

Actually, I was not in favor of organizing it, getting it to another union, but there were a number of people who were.

and they pursued it and just a side note they blamed me for what the council did they somehow had me identified with the council which was ironic since the council had been against us having a self-determining democratic local run by the members and especially the

It was a hell of a fight that I mean I was It was just powerful thing to be a part of that whole thing all these people coming together to fight the power It was it was still invigorating

SPEAKER 3

So then after that you, what did you, you just taught a few more years and then retired or what happened after?

SPEAKER 4

I taught until, oh after the attempted strike.

Yes, I retired in 2006.

So I worked another three years and I trained a replacement to be a steward.

SPEAKER 3

Okay, so then I remember we kept in touch.

We would meet at Clark's over there, Belmont.

Yeah, and then I got you.

I roped you in when I started working for Chicago Public Schools.

We were organizing to get out our long overdue UPC, you know, company unions, you would say at that time.

I remember a fair amount actually.

I'm sure I must have thanked you for inviting me.

I sure hope I did.

SPEAKER 4

I really love the opportunity to be part of more organizing and also to share in the discussions with younger people the issues that inevitably come up between different outlooks, different interests, different perspectives, and different tactics.

So, let me see, hold on one second Jim.

Yeah, I remember being impressed that CORE's starting point was what I consider at such a high level for organizing.

And... What's his name?

What's his name?

Who started the whole thing?

SPEAKER 3

Uh, Jackson Potter?

SPEAKER 4

Yeah, Jackson.

I thought... I was very impressed with Jackson and with the whole group of you.

When you invited me, it was in summer.

and it must have been, it was a relatively small group, I don't know how many people, a dozen?

Right.

Something like that.

And they were like studying, we had to study the things to study, like Shock... Shock Doctrine, right.

SPEAKER 3

Naomi Klein.

Shock Doctrine.

Yes.

SPEAKER 4

We read that to understand how the system works to take away things from working class and ordinary people.

and that was impressive to see that level of preparation.

I remember those discussions and I remember the thing that was exciting about it was that we were following a path of acting as if we were the union even though we didn't have a contract and that the

It was the United Progressive Caucus.

It had been in office for many, many years, their caucus, and they were collaborating or turning their back on the struggle for education and quality education in Chicago public schools.

They were like a business operation.

I remember us preparing in core meetings to intervene to give talks at the Board of Education meetings on specific subjects because they were filmed and people all over the city could see them if they wanted to look them up on public TV.

I remember that we would support each other at these meetings because we would basically be criticizing the board to the board's face.

SPEAKER 3

Yeah Earl, I'll never forget when you spoke to the board as a true fighter for the people.

You looked at the board members and called them agents of capital and that sticks in my mind to this day.

And that's how I, you know, you call them out by their name.

I mean, these were bankers and whatnot on the board of education who are now making decisions for the schools.

SPEAKER 4

Right.

I forgot about that entirely.

So I was a socialist and I thought capitalism was the source of our problems.

So I also was not employed by the public schools anymore, so I had nothing much to lose in any direct sense like that.

Anyway, I remember those things.

and working together in teamwork and people volunteering and stepping up.

Every time somebody would do that, it would encourage others.

So it was, like you were saying, it was exciting for you.

It just showed you that this could be done.

And when you have other people to be looking around the audience to see who's nodding their head, you try and talk to these people afterwards or talk to them after the meeting.

and see what they liked and see if they were interested in meeting you together so you could do it.

The purpose was not to pat ourselves on the back but to organize and to meet people because in a basic outlook course most people have a common interest in having a decent quality education system that teaches people how to have skill but also how to think and how to analyze and how to research and so on and so forth.

So we were looking at it as educators as well as struggling for our own interests.

SPEAKER 3

I do remember because I volunteered and went out to six different schools on the west side including most of the schools on the west side I don't think is here anymore.

SPEAKER 4

Do you remember Jim?

SPEAKER 3

I remember, but I can't remember the name of the high school, it was huge.

Anyway, I went out there with literature like other people went to other schools, and I remember that the assistant principal

SPEAKER 4

She stopped me, called downtown, and I told her we were authorized to distribute union literature and she called the union steward down and I had a chance, the opportunity, to talk to the union steward and she was interested and she basically helped me to pass out the literature to the mailboxes of the teachers there and I had

I was an active campaigner in that sense.

And it was great to be able to make that contribution.

And I was one of many, of course.

SPEAKER 3

Yeah, yeah, that was great.

I remember myself.

Yeah.

So then now, it got now all of a sudden we we we win core all of us as organizers and take power and then you were you played a very important role in the beginning when it was coming up

with the powers that be, because this was at the time of Mayor Daley and privatization, the attack on the schools was ramped up with the whole neoliberal agenda to destroy public schools and put in charter schools and all that.

And then you looked at that deal we talked about a lot, which was the Senate bill was SB7.

And you made a big speech, I remember, at one of our core meetings.

What do you recall about that?

Because your words were important to talk to the people who didn't understand the specifics of the union contract and that bill.

SPEAKER 4

Yeah, Senate Bill 7 was an agreement that, as I recall, Karen Lewis had been invited to be one of the people who

contributed to coming up with this bill.

And the bill, as I recall, set a certain limit that the CTU could only strike if a very high percentage of the members voted to authorize it.

And there were other conditions which made teachers having a union struggle very difficult.

and I think they had limitations on other unions outside of the CTU because most of the teachers in the state were organized through, what was it called?

What's another teachers union?

I can't think of the name.

SPEAKER 3

The IFT?

SPEAKER 4

Yes, the Illinois Federation, no, the Illinois Education Association.

SPEAKER 1

Okay.

SPEAKER 4

Most of the other teachers

So it was in smaller cities.

Anyway, everybody who was negative, who would have been negatively affected by this would have been hurt by the provisions in this.

And I pointed out though, that CORE and union leadership, which is part of CORE elected as part of CORE, could campaign around the state to build a united front

of the different teachers unions, locals, because we faced a common problem and that was the potential of this law being passed.

And it was especially bitter and difficult because Karen Lewis, who's our candidate for president and was elected and was a very strong speaker and had promised to take everything to the membership.

um so most since she's been our candidate for president of the local um I assume that was part of the reason that many people did not want to campaign even though we could have it was totally legal and would have far increased our chances of defeating this bill

That was very controversial and poor, of course.

SPEAKER 3

Yeah, because I remember Earl that SB 7 was sold because it saved the strike.

Karen said it saved our strike, but it was a very high percentage.

You had to get 75% of everybody and that's how she sold it.

But then you said to take a specific look, it was really damaging to our seniority rights and other collective bargaining agreements over the years that they really curtailed.

And you made a very important speech

about that in which Karen and Jesse had to answer to that or at least be held accountable.

SPEAKER 4

They responded, yes.

And I remember at the end of the discussion or debate time, I recall, wait a second, I recall asking for a straw vote to see what the people's opinion was at that time without it being binding or a decision-making vote.

And I remember clearly it was 22 to 11.

22 people were against it and 11 people were for it, including you, as I recall.

And the table at which I was sitting

There were two or three new teachers who had never been to a core meeting before and they were disgusted by the fact that the majority of people were against campaigning to fight SD7 which as you said had numerous causes and aspects that were harmful and the thing about 75% when 75% of the members

Right.

SPEAKER 3

I was going to say that what this led to your, especially your eloquent speech, you're a great speech maker and people listening and understanding better.

This was, it led to after this deal was done, uh, with the legislators, uh, you know, the Democrats, whatnot, that, that passed this bill because of all the pressure from these billionaire groups that were putting pressure on the public schools to make these bad deals.

It then led to.

I believe it was Sarah Chambers who then introduced a resolution in the Executive Board to, I don't know if denounce or just to say that SB 7 is not what we really wanted, to have a different version of it or something to take away the harmful parts of it that you had spoken about, and that upset the people, you know, the Democrats

legislators who had made deals with Karen.

They were very upset about that, but that, you know, just put them on, you know, a notice about making a deal like that in the, in the very beginning with the, with the politicians.

SPEAKER 4

So I remember that I wasn't on the executive board, so of course I didn't know that, but I do recall that they went back down to Springfield and made some changes.

right which were not made in my opinion were not major but they were changes and therefore it gave something to those people who didn't like but I do recall that the leadership of CORE postponed the next month's meeting and then the month following that there was a proposal that was made to oppose my motion and by that time the large majority of the core people was held on a not by hands showing but by voice count.

The clear large majority were against the proposal of fighting it.

and I think there were only three people who voted for it by sound of your voice.

I think it was you and Terry Daniels and somebody else.

I remember being startled by hearing George Schmidt's voice.

We were sitting next to each other by chance and voting against the fight and it just told me that people were very

Anyway, that's what it was called.

Not too long after that, so during the course of this back and forth, both George and Jesse put out emails to the whole list of Core members calling for me to be kicked out of the Core.

I was not too well after that.

I was cut off from the communications.

That's the end of my experience with CORE.

Yeah.

I didn't realize that.

I wasn't in touch anymore.

SPEAKER 3

Let me think for a second.

What could I do?

Oh, I know.

Two years later, I moved out to Elgin, which is where my partner, Sue, was living at.

SPEAKER 4

And she was planning to stay.

And so I moved out here.

We bought a house together, which is where I'm sitting right now while we're talking.

And I joined and I became active with the Fox Valley Citizens for Peace and Justice, a progressive group out here in the Fox Valley, which includes Elgin and other cities in the River Valley.

But I had Parkinson's,

Well, you know Earl it's been fantastic just love you know, like I said, you're you're a hero to us in uh, growing up in the, in the city, getting educated by the rough and tumble politics and radical politics and the, you know, the fight continues.

I was going to say, yeah.

So, um, what would you say your assessment today is, you know, now that we have Brandon Johnson, who was a former organizer for the CTU is, is the mayor. Um, you've got, you know, our union, they say is very, very powerful.

They're playing the political game, which we know is, is ugly.

The people's fight continues.

Any, any thoughts on that right now or anything to finish up?

SPEAKER 4

Let me think for a second, Jim.

I think it’s much harder now.

I don't know.

I think I think as working people I think people face incredible problems that are in the process right now from the climate crisis from the spreading middle east war which since all these things are connected with money and power and inciting and the potential for nuclear war and we're seeing these develop just today's paper um said that in Iran some people planted bombs that killed 100 people at a funeral service of a memorial for one of the Iranian military commanders and said 100 people in the war were killed and it's clearly related to the fight that Israel is waging in Gaza against Iraq and much of the population.

It's just... And the third thing that I think is massive in facing people is the economic situation of the U.S. and the world.

And the short version of that is that if the dollar becomes less and less powerful and influential,

It means that if you have dollars coming to you like a retirement plan which I get for my 27 years those dollars are basically fixed but what the dollar will buy becomes less and less and we call it inflation but it is hardship and it's going to take more and more radical measures to stop, and U.S. life expectancy for men has been falling for the last 10 years as an indication of growing hardships.

And the only hope that I have lies in the positive aspects of my experience, which includes reading and studying Marx and others in discussion groups.

Vail

It's been wonderful talking to you.

Just an amazing story you have to tell.

All the, you know, the times, I want to just big thank you to everything you've, you've meant to me and to all of us in the, you know, the fight for, to save, public education, fight for a better world, the revolution, politics, how we see the world, keep that fight alive.

And so I'm just hoping that people, you know, listen to this and take note about how to, how to go about it, how to, how to fight the system and, and, you know, keep on fighting.

I'm very happy you are happily retired and you're traveling a lot and taking it easy.

SPEAKER 4

I'm not traveling so much anymore as soon as I was, but thanks for the compliments.

If I could add one thing, I would say the most important and most commonly hidden aspect of struggles is that groups of people who agree with the biggest perspective play a necessary role. They're called caucuses or political parties but these things don't happen by themselves as you and I know from our experience.

And the other reason that the CTU has become a more powerful force is because a handful of people organized CORE and CORE people went out and talked to more teachers and organized as if we were the union and this is a never-ending development and looking to organize groups, no matter how small, with a common perspective is an absolutely necessary ingredient.

That's all I have.

SPEAKER 3

All right, perfect.

That's a great way to end.

So thank you again, Earl.

Thank you, Jim.

Yep.

Okay.

Take care.

SPEAKER 4

You take care too.

SPEAKER 1

Thanks so much.

Yep.

Bye-bye.